Proving Roman Citizenship: Rights, Identity, and Documentation in the Ancient World

Updated on: 02 February 2025Reading time: 10 minutes

In Ancient Rome, passports, ID cards, and other modern forms of identification did not exist. How did the Romans prove their citizenship in a world without photographs, biometrics, or computers?

Proving Roman citizenship was crucial in Ancient Rome. Citizenship determined one’s rights and could even mean the difference between freedom and slavery. While slavery is considered immoral today, in the ancient world it was the norm rather than the exception. In the early 1st century AD, only about five million of the over fifty million inhabitants of the Roman Empire were free and full Roman citizens1.

Roman Citizens Had Many Privileges and Rights

Being a Roman citizen was akin to being part of an exclusive club with numerous privileges and rights. A citizen enjoyed benefits that a non-citizen or a slave did not. Most importantly, he had the right to be free. He also had the right to vote and to serve in the military. He could partake in various forms of Roman entertainment, such as public performances in theatres. Citizens were exempt from certain taxes, such as the land tax levied in the provinces1. Furthermore, they had the full protection of Roman law when facing justice in provincial cities outside Italy, when making legal contracts, buying or inheriting property, or getting married. Roman law did not recognise marriages between non-citizens or between a citizen and a non-citizen (matrimonium injustum, non legitimum). A Roman citizen was also spared extreme punishments, including torturous executions such as crucifixion.

|

Various Levels of Roman Citizenship

Roman citizens were generally held in higher esteem than non-citizens, even if they had a slave background. However, different levels of citizenship existed, each with varying rights:

Cives Romani: Full Roman citizens, subdivided into two groups: non optimo iure, who had rights of property and marriage, and optimo iure, who also had the right to vote and hold office.

Latini: Originally referring to the Latin tribes of central Italy, who came under Roman control at the close of the Latin War (340–338 BC), the term later expanded to include non-Latin people under Roman control. They had some rights akin to Roman citizens (Latin Rights or ius Latii) but lacked the right of marriage (ius connubii).

Socii: These were citizens of states allied with Rome (Foederati), who enjoyed certain rights in return for military service.

Following the Social War (91–88 BC), the Lex Julia of 90 BC granted full Roman citizenship to all Latini and Italian socii states (except those that had rebelled), effectively eliminating these intermediate levels of citizenship.

Provinciales and Freedmen: The provinciales were people from Roman-controlled provinces who had only basic rights under international law (ius gentium). Freedmen were former slaves who had gained their freedom but were not automatically granted Roman citizenship. However, their children were born as free citizens.

A Web of Relationships and Culture Rather Than Paperwork Proved Citizenship

Romans did not carry ID cards or documentation proving their citizenship at all times. Instead, a person's web of relationships and position in society established their status. A Roman citizen was typically a member of a family, tribe, and gens (clan). If someone's parents were citizens, their own status was usually unquestioned.

Roman citizens, particularly those of higher social standing, were expected to participate in state affairs and hold public office—positions reserved for citizens. Consequently, citizenship was often self-evident. When in doubt, social networks provided verification. In a society where literacy was the exception rather than the norm, reputation and word of mouth were paramount, particularly in small towns.

Language and clothing also played a role in identifying Roman citizens. Someone who spoke fluent Latin, behaved in a distinctly Roman manner, and dressed appropriately signalled their status. The toga was exclusive to Roman citizens, and non-citizens, foreigners, freedmen, and slaves were forbidden from wearing it. Even men of disreputable professions (such as actors) or those of shameful reputation were prohibited from donning the toga.

Roman Names as a Marker of Citizenship

Roman names were a clear indicator of citizenship. A traditional Roman male name consisted of three parts (tria nomina):

- Praenomen (personal name, used within the family)

- Nomen (clan name)

- Cognomen (originally a nickname, later hereditary)

For instance:

| Gaius | Julius | Caesar |

| praenomen | nomen | cognomen |

| Marcus | Licinius | Crassus |

| praenomen | nomen | cognomen |

| Publius | Cornelius | Scipio | Africanus |

| praenomen | nomen | cognomen | agnomen |

Scipio Africanus gained his cognomen due to victories in Africa.

In 24 AD, it became a criminal offence for a non-citizen to adopt the tria nomina, and doing so was considered a form of forgery. Provincials typically had one or two names (their own and their father’s), while slaves often had only one, either their original name or one assigned by their master. Upon gaining freedom and citizenship, a slave took his master’s praenomen and nomen but kept or modified his cognomen to sound more Roman1.

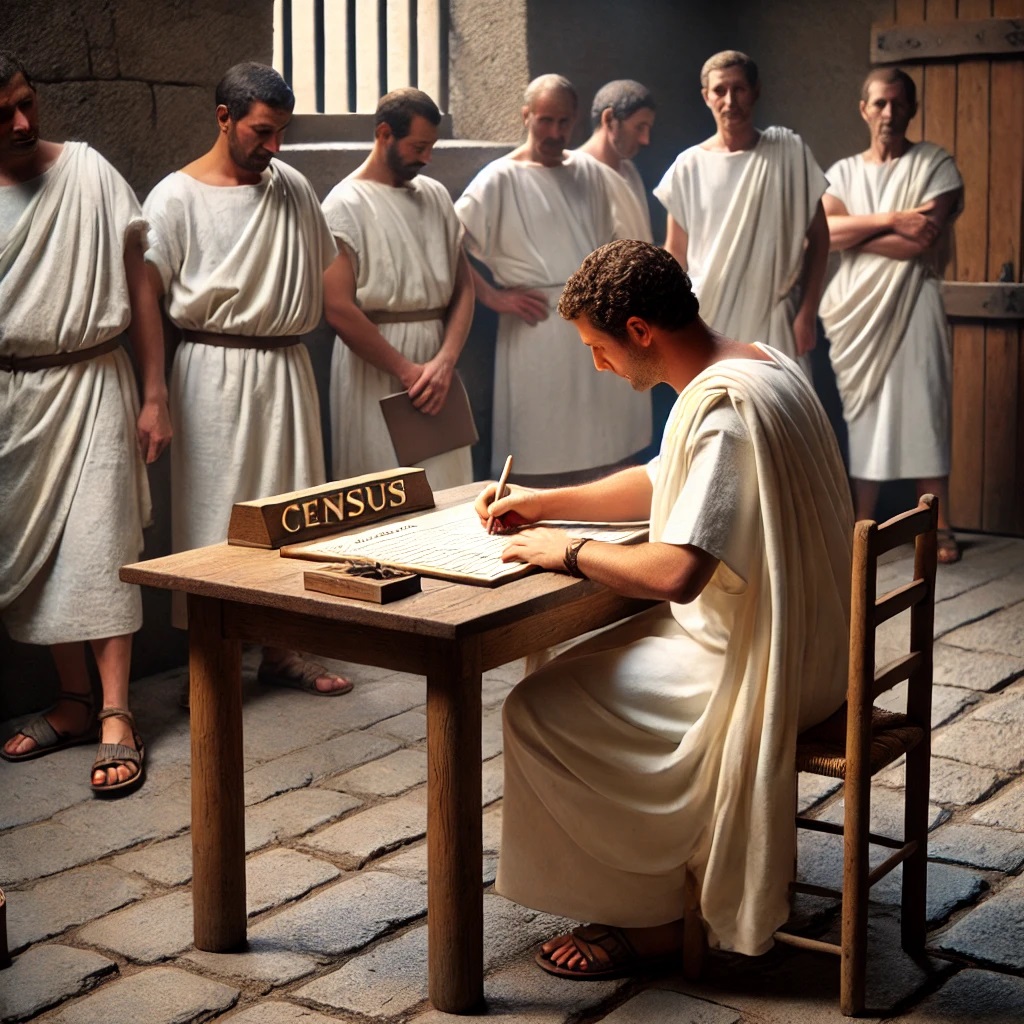

Tribal Lists, the Roman Census, Birth Certificates, and Citizenship Grants

The census (censere) was conducted every five years to register Roman citizens and their property for tax purposes. The first census dates to the 6th century BC under King Servius Tullius, recording approximately 80,000 citizens. The censor, an official responsible for maintaining the census, also supervised public morality (regimen morum), hence the modern term "censorship." The censor's power was absolute, and no other magistrate could challenge his decisions.

Citizenship records were maintained through tribal lists, in which a paterfamilias declared under oath before the censors the members of his household, including the number of slaves, as well as the location and description of his property. These records, the Tabulae Censoriae, were stored in the public treasury (aerarium).

If a person's Roman citizenship was in doubt, or if proof of citizenship was required for a transaction, an inquiry could easily be made to verify their name on the most recent census list. Witnesses, typically fellow members of their tribe, would also be called upon to confirm the individual's identity—keeping in mind that photographs or other visual records did not exist at the time.

Occasionally, a freedman (libertus) or even a foreigner attempting to pass as a Roman citizen by wearing a toga was discovered during the census. The punishment for falsely claiming Roman citizenship was severe. According to Suetonius, the penalty was execution—by decapitation with an axe. The Romans took citizenship extremely seriously, and any fraudulent claim was met with the harshest consequences.

|

Birth certificates

Birth registration was introduced during the reign of Emperor Augustus (27 BC–14 AD) in 4 AD. A Roman citizen was required to register his child's birth within thirty days before a Roman official. Unlike the census, this registration was not mandatory, and failure to register did not result in the loss of Roman citizenship.

Upon registration, the citizen received a wooden diptych with waxed surfaces on the inside, serving as both a birth certificate and proof of citizenship for the child. The diptych measured seven inches in height and six inches in width. Inscribed on the waxed surfaces were the date of birth, the names of seven witnesses, and the abbreviation q. p. f. c. r. e. ad k. (with c.r.e. signifying cieum romanam/num exscripsi/t), indicating Roman citizenship. This diptych could be used throughout life as evidence of citizenship and was written solely in Latin until the reign of Emperor Severus (222–235 AD).2.

If a child was born in the provinces, his father or an appointed agent made a declaration (professio) before the provincial governor at the public record office (tabularium publicum). During this professio, the father or agent affirmed that the child was a Roman citizen. The professio was then entered into the register of declarations (album professionum)3. The father or agent was subsequently issued a wooden diptych, which served as the official certified private copy of the professio and contained the names of seven witnesses.

a Boian soldier of the Ala CC BY-SA 3.0 |

Grants of Citizenship for Soldiers, Provincials, and Freed Slaves

From 52 AD onwards, non-citizen (peregrini) auxiliaries serving in the Roman army were granted Roman citizenship upon completing 25 years of service. They received a diploma civitatis, a certificate consisting of two bronze plates joined together. The outer side of the first plate confirmed that the holder had served in the Roman military and had been granted Roman citizenship, while the outer side of the second plate bore the names of seven witnesses. The text engraved on the outer surfaces was identically reproduced on the inner sides. The plates were then sealed together, with the seals protected by metal strips.

A veteran retiring in the provinces would present the sealed diploma at the public record office, where an official would break the seals and verify that the internal inscriptions matched the external ones. Once confirmed, the official would register the veteran’s name in the list of resident Roman citizens.

A freed slave would adopt the praenomen and nomen of his former master while retaining his cognomen, which had been his name as a slave, unless he chose to change it to a more Latin-sounding name1. The enfranchisement of freedmen was recorded in a formal document known as the tabella manumissionis4. Thus, freedmen also possessed official documentation confirming their status.

Travel and Proving Citizenship Abroad

Most Roman citizens did not travel extensively. Ancient Rome and the broader ancient world were vastly different from today’s globalised society. In Ancient Rome, mobility was uncommon, especially for the working classes, and long-distance travel was primarily undertaken by soldiers and merchants. Furthermore, most travel took place within Roman-controlled provinces. Venturing beyond Rome’s territories was rare, as it carried significant risks, including the possibility of capture and enslavement—unless the traveller had connections capable of offering protection.

To prove their Roman citizenship while abroad, Romans could present their grant of citizenship or birth certificate, both of which were recorded on a diptych—small and portable enough to be carried when travelling1. If doubts arose regarding a person’s claim to citizenship or the authenticity of their document, witnesses could be called upon to verify their identity5.

However, securing witnesses in distant provinces was not always straightforward. A notable example is the case of Gavius in 70 BC. Verres, the corrupt governor of Sicily, challenged Gavius’ claim to citizenship. Gavius, a Roman citizen from Compsa, had protested against Verres' mistreatment of Roman citizens. According to Cicero, Gavius repeatedly asserted that he was a Roman citizen and had served in the Roman army under the Roman knight Lucius Raecius, who was in Panhormus (modern-day Palermo) at the time. Despite his claims, Gavius was executed by crucifixion—an execution method strictly forbidden for Roman citizens6.

Verres eventually faced trial for his actions. This case illustrates that, in the Roman world, a citizen’s social network often held greater significance than their legal status. A Roman citizen’s connections could determine the consequences imposed on those who mistreated them. Provincial governors and foreign authorities were wary of potential repercussions before mistreating any Roman citizen, particularly those of the upper class. More than official documentation, it was a citizen’s social standing and influential connections that provided the greatest protection.

The Role of Documentation in Preventing Slave Escapes

Documentation also made it significantly more difficult for a slave to escape. A runaway slave would typically have to flee a considerable distance—and quickly—to avoid immediate capture. As soon as a slave went missing, notices detailing their precise description would be displayed in public places, with rewards offered for their return. Professional slave-catchers were often hired to track them down, and anyone found harbouring a runaway slave faced severe punishment.

Beyond evading capture, an escaped slave had to secure food, shelter, and employment. Even if they managed to reach a new town or a large city like Rome, their identity would inevitably be questioned—at the very least during the census, which took place every five years. At that point, they would be required to provide documentary proof of their status. Failure to do so risked exposure, as slaves were generally illiterate and unable to forge documents convincingly.

If caught and not executed, an escaped slave would be branded on the forehead with the letters FUG (fugitivus), marking them permanently as a runaway. Despite these immense risks, some slaves did manage to escape to distant provinces. However, the journey was perilous, with dangers at every turn.

Conclusion

Passports, ID cards, and other modern forms of identification did not exist in Ancient Rome. However, the Romans had birth certificates, grants of citizenship, and military diplomata, which they could carry as proof of citizenship. Ultimately, what mattered most was a person's social network, which could confirm their status and reputation and offer protection in the provinces.

Even though modern identification methods were absent, it was still difficult to falsely claim Roman citizenship in a society where people were familiar with each other's backgrounds and where travel was rare. The Romans took citizenship extremely seriously, and the punishment for falsely claiming to be a citizen was so severe that few dared to risk it.

Incredible facts about Roman citizenship

|

SOURCES

- The Greco-Roman World of the New Testament Era: Exploring the Background of Early Christianity (James S. Jeffers, IVP Academic, 1999)

- Roman Registers of Births and Birth Certificates. Part II. (Schulz Fritz, The Journal of Roman Studies Vol. 33 parts 1 and 2, 1943)

- Paul: Apostle of Free Spirit (F.F. Bruce, Exeter:Paternoster, 1977)

- The Roman Citizenship (Sherwin-White, 2d ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973)

- The Book of Acts and Paul in Roman Custody (Brian M. Rapske, Eerdmans, 2004)

- The Verrine Orations I: Against Caecilius. Against Verres (Cicero, Part I Part II Books 1-2 Loeb Classical Library, 1928)

- Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture (Jonathan Edmondson, University of Toronto Press, 2009)

- The Roman Censors: A Study on Social Structure (Suolahti, J. 1963)

- Being a Roman Citizen (Jane F. Gardner, Routledge 1 edition, 2010)