Ancient Roman Aqueducts: Engineering Marvels, Uses, and Lasting Legacy

Updated on: 16 February 2025Reading time: 5 minutes

Even though aqueducts had existed in the Near East for centuries before the construction of Rome’s first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, in 312 BC, Rome was the first civilisation to use water so extensively in its cities. The Romans had fountains, public and private baths, latrines, and a sophisticated sewage system—remarkable for its time. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, it took many centuries for European towns and cities to develop such an advanced water system again.

Ancient Roman aqueducts were built to transport water from distant springs and mountains into cities and towns. This water supplied the city's fountains, gardens, public baths, latrines, and the homes of wealthy Romans, which were equipped with private baths and latrines. Aqueduct water was also used for agricultural and industrial purposes, such as irrigating land, powering mills, and operating machinery in mining, among other applications.

Aqueducts contributed to urban cleanliness through an advanced sewage system and helped maintain personal hygiene. Romans of all social classes bathed in public baths, and it was not uncommon to bathe daily. With a typical workday lasting six hours, many Romans visited the public baths in the afternoon to relax and socialise.

How Ancient Roman Aqueducts Were Built

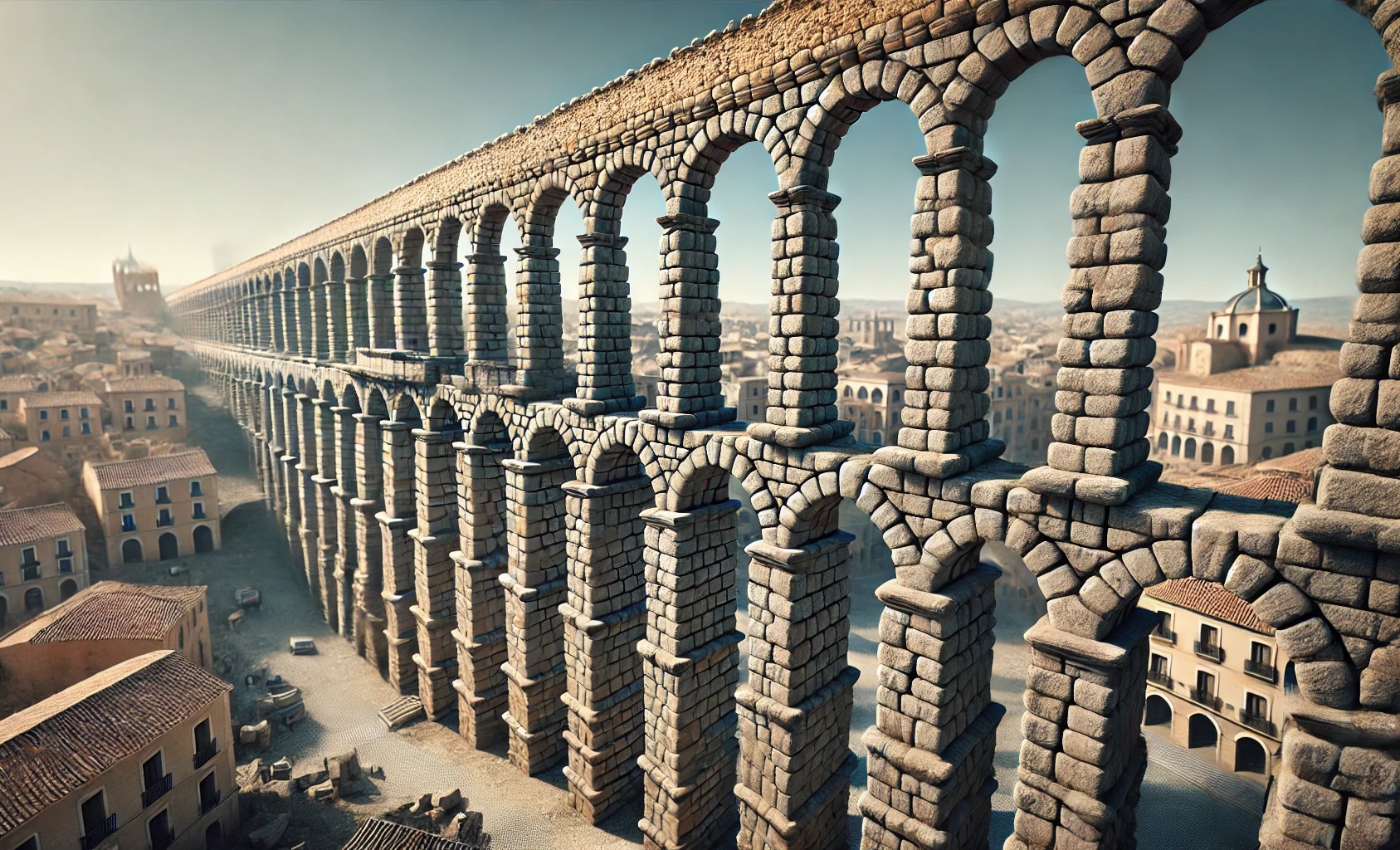

Ancient Roman aqueducts were a remarkable feat of engineering. People from abroad or rural villages would come to Rome and stand in awe before these towering arches stretching for miles. The technology involved in their construction was highly advanced for the time. Roman aqueducts did not use pumps but relied solely on gravity. They were built with a slight downward gradient and sometimes extended for over 100 kilometres (62 miles)!

|

Most aqueducts were constructed below the surface (typically 0.5 to 1 metre, or about 3 feet deep), but as they reached valleys and the outskirts of cities, they rose above ground in the form of bridge-like structures. Engineers used tools such as the chorobates to ensure precise horizontal alignment. Many of the pipes were made of lead, though the Romans were already aware of the dangers of lead poisoning. As a result, ceramic and stone were often preferred over lead. The Romans also introduced several innovations, including large storage tanks built at intervals to regulate the water supply and the use of waterproof concrete.

Ancient Roman aqueducts were highly reliable, as evidenced by the many still standing today, such as the Pont du Gard in France and the Aqueduct of Segovia in Spain. These structures attest to their durability. However, aqueducts fell into disuse mainly because they were destroyed or left unmaintained following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

The first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, was commissioned in 312 BC when Rome faced a water shortage. At the time, people relied on local springs, public and private wells, and rooftop cisterns to collect rainwater. The Aqua Appia sourced water from a spring 16.4 kilometres (about 10 miles) from Rome and supplied the city’s main trading centre and cattle market. The second aqueduct, the Anio Vetus (Old Anio), was built 40 years later. The third, the Aqua Marcia, was constructed between 144 and 140 BC and was the longest aqueduct in Rome. It ran for approximately 91 kilometres (57 miles) underground and 10 kilometres (6 miles) above ground on arcades before reaching the city.

Many more aqueducts were built, particularly during the Roman Empire. By the 3rd century AD, Rome had eleven aqueducts. The quality of the water they supplied varied—some delivered excellent drinking water, while others were prone to contamination, especially after heavy rainfall. Roman aqueducts required regular maintenance, as leaks could develop over time and debris could accumulate in the conduits. To address this, access points were installed at regular intervals along the underground sections of the aqueducts.

Aqueducts for Private, Agricultural, and Industrial Uses

Private users could connect pipes from their property to an aqueduct, provided they obtained a licence and paid a fee based on the width of the pipe. These pipes bore inscriptions detailing information such as the manufacturer, the fitter, the subscriber, and the entitlement. However, illegal tapping was common. Aqueduct officials and workers were often bribed to allow pipes to be widened or unlawfully connected to the aqueduct. Although illegal tapping could, in theory, be punished by the seizure of assets, the law was rarely enforced. Some of the wealthiest Romans bypassed the public system entirely by purchasing water access rights to springs and constructing their own private aqueducts to supply their villas.

Science Museum |

Ancient Roman aqueducts were also essential for agriculture. Farmers without access to a spring or river could purchase a licence to draw a specific quantity of water, which was used for irrigation and to provide drinking water for livestock. However, these licences were difficult to obtain, particularly in rural areas. While illegal tapping could result in the confiscation of assets—such as land or agricultural produce—the law was rarely enforced, as increased farm production helped keep food prices low. Instead of seizing assets, authorities often chose to tax farm produce instead.

Aqueducts also had significant industrial applications, particularly in mining. Channels were cut into the ground at a steep gradient to deliver large volumes of water at high pressure to the mines. This water was used for hushing—a technique where torrents of water washed away soil and rock to expose ore—and to power machinery such as waterwheels, which in turn operated stamps and trip hammers used to process the ore. Evidence of such mining operations can be found in Rome, Athens, Spain, Dolaucothi in Wales, and Barbegal in Fontvieille, France.

Incredible facts about ancient Roman aqueducts

|

SOURCES

- The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World (J.P. Oleson, Oxford University Press, 2012)

- On Architecture (Vitruvius, Penguin Classics, 2009)

- Ancient Water Technologies (L. Mays, Springer, 2010)

- Gardens and Neighbors: Private Water Rights in Roman Italy (C. Bannon, University of Michigan Press, 2010)

- Aqueducts of Rome (Frontinus, Harvard University Press, 1925)

- Roman Aqueducts and Water Supply (A. T. Hodge, Bristol Classical Press, 2002)