Ancient Roman Banking: Temples, Money Changers, and Financial Innovation

Updated on: 31 December 2024Reading time: 7 minutes

As incredible as it may sound today, temples consecrated to the ancient Gods were also the first banks in ancient Rome. Many temples, especially those located in and around the various Fora, housed State treasures and the wealth of affluent Romans in their basements. Notably, other civilizations, such as those in Mesopotamia and ancient Greece, also used their temples to store treasure and money.

To illustrate how unusual this may seem today, imagine churches and cathedrals equipped with large underground safes, where people might go to pray and... withdraw money.

Wikimedia Commons CC SA 4.0 |

Because temples were staffed by priests and devout workers, and often heavily guarded, they were regarded as depositories of unquestionable security. Wealthy Romans commonly stored their money in multiple temples across various locations, ensuring easy access without the burden of carrying it around. Diversifying their deposits also minimized the risk of losing their entire fortune in case of a fire or attack on a particular temple.

Thousands of temples across Roman territories doubled as repositories. The Temple of Saturn in Rome, still visible today, housed the Aerarium or Rome's public treasury. The Temple of Castor and Pollux served as the State treasury during the imperial period. Some temples, such as the Juno Moneta temple, even minted money.

During the Empire, however, public deposits increasingly shifted to private repositories rather than temples.

Roman Money Changers

Priests were, in essence, also bankers. They managed deposits, issued loans with interest, and engaged in currency exchange and validation. They could even forgive debts entirely.

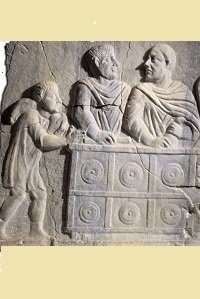

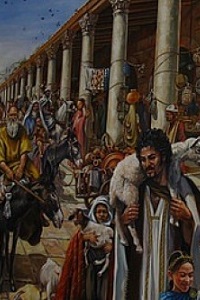

In addition to priestly bankers, there were other types of bankers in ancient Rome. The argentarii, or money changers, played a significant role as commerce and trade expanded across the Mediterranean from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD. The image of Jesus overthrowing the money changers' tables in the temple in Jerusalem comes to mind. Argentarii operated shops and stalls in the Forum, close to the major temples.

The earliest money changers, known as trapezites (from the Greek word trapeza, meaning "counter"), were Greek bankers conducting transactions in counting houses. They exchanged drachmas for sesterces or vice versa, as Greek commerce dominated the Mediterranean during the early Roman Republic. Over time, the term trapezites was replaced by the Latin term argentarii (also known as argenteae mensae exercitores, argenti distractores or negotiatores stipis argentariae), or Roman money changers.

|

The argentarii were private, independent individuals belonging to a guild with limited membership. Their shops or stalls around the Forum were state-owned and built by the censors. Their primary function was currency exchange (permutatio in Latin), but over time, they expanded to include a wide range of financial activities, such as holding deposits, lending money, participating in auctions, and authenticating coins.

The reputation of argentarii’s varied. Those conducting large-scale operations with wealthy clients were highly respected and often belonged to the upper class. Conversely, those engaging in usury or small-scale, questionable transactions were often looked down upon.

Public Bankers: The Mensarii

During times of widespread poverty, often during wars, citizen indebtedness became a significant threat to the Republic's stability. In ancient Rome, inability to repay debts could lead to slavery for the average citizen.

To address this issue, public bankers called mensarii were introduced in 352 BC. A five-man commission, the quinqueviri mensarii, was established alongside a public bank. The commission provided funds from public resources to citizens who could offer sufficient security, such as property. Those unable to offer adequate security forfeited their property to creditors after official valuation.

In 216 BC, a three-member commission with expanded functions was established. Although often confused with the argentarii, the mensarii were public bankers. Over time, their functions resembled those of the argentarii, including holding deposits, authenticating coins, and more. However, the mensarii enjoyed an excellent reputation and were highly respected for their role in alleviating excessive debt and resolving citizens' financial difficulties.

Mint Officers: The Nummularii

The nummularii managed a bank responsible for circulating new coins. They exchanged old or foreign coins for new ones and ensured the quality of newly minted coins.

The nummularii were also involved in significant financial transactions, verifying the authenticity and value of coins. Many of their duties overlapped with those of the argentarii, such as holding deposits, lending money, facilitating auctions, and executing payments abroad through local bankers.

Conclusion

Banking in ancient Rome was remarkably sophisticated, paralleling many modern banking practices. From the widespread use of credit and foreign exchange to the recording of transactions, Roman banking reflects the advanced nature of Roman society.

Functions of the Argentarii

|

SOURCES

- Banking and Business in the Roman World (J. Andreau, Cambridge University Press, 1999)

- Mensarii, bankers acting for public and private benefit (P. Niczyporuk, the Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2011)