A Culinary Journey Through Ancient Roman Food: Tastes, Preservation, and Traditions

Updated on: 01 January 2024Reading time: 7 minutes

During the Roman Kingdom (753 BC – 509 BC), Roman food mirrored the simplicity of ancient Greek cuisine. At that time, the staple diet consisted of a porridge known as puls, crafted from emmer, olive oil, salt, and an assortment of herbs. Beyond puls, the Romans incorporated cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruits, meats, fish, and seafood into their culinary repertoire. Their cuisine was enhanced with olive oil, vinegar, salt, pepper, mint, saffron, and an array of spices.

Roman cuisine during the Republic and Empire

The evolution of Roman cuisine unfolded significantly during the Republic and Empire. Rome's expansion and its assimilation of foreign culinary practices catalysed a shift from a Greek-influenced diet to a diverse and sophisticated culinary culture. As Rome expanded, class distinctions in eating habits became more conspicuous, nurturing the development of a more refined Roman cuisine.Initially introduced by the Romans, the practice of eating three meals a day was primarily embraced by the upper class. In contrast, the majority of people in the ancient world typically consumed just one meal daily. The Roman dining structure encompassed the jentaculum (breakfast), cena (lunch), and vesperna (evening dinner). Breakfast was modest, often comprising a piece of bread accompanied by honey or cheese. Lunch represented the principal meal of the day, while dinner was a lighter affair. As Rome prospered, the availability of diverse foods increased, leading to alterations in meal timings and compositions. The cena transitioned to a larger meal served in the afternoon (2 - 3 p.m.), while the vesperna gradually vanished. Lunch was substituted by the prandium, resembling a light midday meal. Over time, the cena evolved from a single-course meal into a three-course extravaganza: appetizer (gustatio), main course (primae mensae), and dessert (secundae mensae) by the end of the Republic.

Eating habits differences between social classes

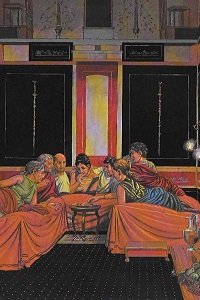

The eating habits between social classes exhibited stark disparities. Wealthy Romans indulged in three daily meals, notably partaking in the opulent cena following afternoon baths. This dinner affair, elaborate and protracted, often extended into the night, accompanied by post-meal drinks (comissatio). Conversely, average Romans typically concluded their day with a light evening supper, the vesperna. These individuals, including slaves, dined while standing or sitting around a table, in contrast to the affluent, who reclined on couches within luxurious triclinium rooms. The expense of such lavish rooms and the necessary oil lamps for illumination at night remained beyond the means of regular Romans, who retired early to accommodate early morning work schedules.

|

Moreover, a conspicuous divide lay in the availability of foods between the upper and lower classes. The average Romans struggled to afford meats and exotic provincial foods enjoyed by the affluent. For instance, while both classes consumed puls, the wealthy enhanced it with chopped vegetables, meats, cheese, and various herbs. Dining for the upper class constituted a luxurious and entertaining experience, while for most Romans, it remained a practical necessity.

Ancient Roman cuisine: The Flavor Palette of Ancient Rome

Roman culinary delights often embodied a unique sweet and sour taste reminiscent of modern-day Asian cuisines. Their penchant for infusing fruits, honey for sweetness, and vinegar for sourness into various dishes created this distinct flavour profile. Efforts to replicate Roman recipes have revealed not only the healthiness of their food but also its delectable taste, quite unlike the flavours we experience today.Bread: A dietary mainstay across all social strata in ancient Rome, bread was a pervasive element of their diet. Pompeii's archaeological discoveries, featuring over 30 bakeries and an abundance of rotary mills grinding grain, attest to the Romans' significant consumption of bread. It was commonly paired with honey, olives, eggs, cheese, or moretum, a spread concocted from cheese, garlic, and assorted herbs. Salting bread and dipping it in wine were customary practices. Originally crafted from emmer, a wheat relative, bread gradually transitioned to wheat during the Empire, mirroring contemporary bread. However, Roman flour was coarser, laden with dust and grainy bits, which over time wore down people's teeth due to prolonged chewing.

Legumes, Vegetables, and Fruits: Ancient Romans extensively cooked legumes like beans, peas, and lentils, incorporating these nutritious items into their diets. A bounty of vegetables and fruits, either raw or cooked, adorned their tables. Notably, some produce integral to Mediterranean cuisine today, such as tomatoes, potatoes, and capsicum peppers, emerged post the New World discovery in the 1400s. Eggplant arrived in 600-700 AD through Arab influence, while lemons and oranges were absent until the Principate (395 – 496 CE), with lemons starting cultivation during this period. Think of vegetables like cabbage, celery, kale, broccoli, radishes, asparagus, yellow squash, carrots, turnips, beets, green peas, cucumber, and fruits such as apples, figs, grapes, pears, and olives as the staples of ancient Roman diets. Noteworthy are the varied colours of carrots, unlike the common orange variant today, which have become extinct.

Meat and Fish: Fish and seafood, more accessible and affordable than meat, were prevalent in Roman diets. They relished fish varieties like sardines, tuna, sea bass, along with shellfish and octopus. Rome boasted flourishing fisheries and aquaculture, with a robust industry in fish and oyster farming. Poultry like chicken and game were also commonplace. While meats like (salted) pork and lamb were deemed luxurious, beef was less prevalent (more common in ancient Greece). Wealthier Romans displayed opulence by serving delicacies like rodents, particularly dormice, as a status symbol, even weighing them in front of guests before preparation.

Garum: A cornerstone of Roman culinary culture, the fish sauce garum featured prominently in numerous dishes, both for cooking and as a table condiment. Crafted from small fish intestines, garum imparted a distinctive flavour to their cuisine.

Romans and Their Drinks: A Taste of Ancient Imbibing

Wine: Despite access to high-quality aqueducts water, Romans preferred alcoholic beverages over water due to potential taste issues or bacterial contamination. Wine reigned supreme among their drinks, but it diverged from modern consumption practices. With a higher alcohol content, it was customary to dilute wine before imbibing, considering it uncivilised to drink it straight. The Romans infused various spices and honey, often serving it hot, and stored it in amphoras, not glass bottles.Posca: A beverage despised by the upper class, posca was favoured among plebeians and the military. Crafted from acetum or low-quality wine verging on a vinegar-like taste, posca often utilised spoiled or improperly stored wine. Diluted with water and enhanced with crushed coriander seeds and occasionally honey for sweetness, posca was a staple drink for this demographic.

Beer: Though wine and posca dominated across the Roman Empire, beer (cerevisia in Latin) and honey mead found more traction in Northern provinces. However, beer consumption was deemed barbaric in Rome and associated with outsiders, akin to the perception of milk as barbaric, reserved primarily for cheese-making.

Non-existent Drinks: Many beverages common today were absent in ancient Rome. Coffee, now synonymous with Italy, only appeared in the 16th century and had its roots in Arab culture. Tea, an Asian import introduced by the Dutch in the 17th century, also didn't exist. Therefore, envisioning the Roman world entails a landscape devoid of tea, coffee, milk, or orange juice.

The Culinary Center: The Focus in Roman Kitchens

The focal point of well-to-do Roman homes was the focus, an open hearth used for cooking, akin to medieval homes. Positioned before the lariarium, a shrine for household guardian spirits—lares and penates—daily rituals honoured these deities. Portable, often marble or stone-legged, with a cauldron suspended by chains above the fire, the focus evolved with the rise of separate kitchens in affluent households.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic |

With the advent of distinct kitchens, the focus transitioned into a space solely reserved for religious offerings or house warming. Pompeii's kitchens were usually compact, except for exceptions like the Villa of the Mysteries, featuring a larger 3 by 12-meter area. Equipped with ovens shaped like domes or squares made of brick and various utensils—knives, forks, pans, pots, molds, measuring jugs, graters, sieves, cheese-slicers, and tongs—fashioned from bone, wood, bronze, or iron.

For most Romans, a separate kitchen was a luxury, resulting in shared kitchen spaces and communal ovens. Open-air cooking was common in Roman cities and towns, with Pompeii displaying numerous open kitchens adorned with dome-shaped brick ovens, offering a glimpse into ancient culinary practices.

Preservation of Roman Food: Ancient Techniques and Culinary Insights

In the absence of modern refrigeration, preserving food in ancient times posed a persistent challenge, often resulting in food poisoning and fatalities. Yet, the Romans exhibited remarkable advancements in food preservation. Instead of freezing, meats and fish were smoked and salted. This meticulous process commenced with pickling, often immersing the meat in vinegar, followed by drying, exposure to wood smoke, and finally salting. Live fish and shellfish were also maintained in tanks. While fruits were relished fresh during summer, they were dried to sustain through winter, unlike today's access to fruits year-round from the southern hemisphere.Food preservation wasn't solely about preventing foodborne illness; it also fuelled trade expansion during the Republic and Empire. Many imported foods had to endure long journeys, spurring innovations in preservation methods. For instance, oysters from Brittany were transported in tanks to Italy, while ham from Gallia Belgica (modern-day Belgium) was preserved through smoking and salting, enabling its weeks-long shelf life. Exotic animals like wild game from Tunisia were shipped alive in cages on vessels.

For more insights into ancient Roman cuisine, explore our Roman cook book.

Fascinating Insights into Roman Food Culture:

|

SOURCES

- Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome (Patrick Faas, University of Chicago Press, 2005)

- Roman Cookery: Ancient Recipes for Modern Kitchens (Mark Grant, Interlink Publishing, 2008)

- Roman Life (Early Civilizations) (John Guy, Barron's Educational Series, 1999)