From Lunar Cycles to Leap Years: The Story of the Ancient Roman Calendar

Updated on: 4 January 2025Reading time: 6 minutes

The word calendar originates from the Latin word kalendae, meaning the first day of the month. This was the day when priests proclaimed the new moon from the Capitoline Hill in Rome. It was also the day when debtors were required to pay their debts recorded in the kalendarium, from which the word calendar is derived. Calendars were essential for organising days for religious, administrative, and commercial purposes, as well as for planning agricultural cycles. For instance, the beginning of the year in the Roman calendar marked the start of the agricultural season. The last day of the week was when farmers brought their produce to the city market.

The earliest Roman calendar was lunar, modelled on Greek lunar calendars, where months began and ended with the new moon. Since the interval between new moons averages 29.5 days, the Roman lunar calendar alternated between 29 and 30 days. It comprised 304 days, divided into ten months starting in March and ending in December (from decem, Latin for ten). The winter days between December and March were not assigned to any month.

The second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius (reigned 715–673 BC), introduced the months of Ianuarius (January) and Februarius (February), extending the year to 355 days. Months generally had either 29 or 31 days, with February (28 days) being the exception. This adjustment still left the calendar misaligned with the solar year, or tropical year. To address this, days were periodically added to February, which was divided into two parts. The first part ended with the Terminalia on the 23rd, a festival honouring Terminus, the god of boundaries, marking the end of the religious year. The second part consisted of the five days from the 23rd to the 28th. A leap month, Mensis Intercalaris, was occasionally inserted (usually every other year) between these two parts, helping to re-align the calendar with the solar year.

This system was imperfect, and in 46 BC, Julius Caesar (100–44 BC) introduced the Julian calendar, comprising 365 days and starting on 1 January. Due to the axial precession—a phenomenon discovered by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus—the solar year is about 20 minutes shorter than the Earth’s orbital period around the Sun. To mitigate this discrepancy, an extra day was added every four years, creating a leap year. Emperor Augustus (63 BC–14 AD) further refined the system by adding a leap day to February, making the average year length 365.25 days. However, this still caused a slight misalignment, with the calendar gaining roughly three days every four centuries.

The Gregorian calendar, introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, resolved this issue. It omitted the leap day in years divisible by 100 but not by 400. For example, 1900 was not a leap year as it is divisible by 100 but not by 400. Conversely, the year 2000 was a leap year, as it met both criteria.

Meaning of the Names of Days and Months in the Roman Calendar

The modern calendar honours Roman rather than Christian deities, with several months named after Roman gods. For example, March, the first month in the ancient Roman calendar, honoured Mars, the god of war. The origin of April (Aprilis in Latin) is unclear; some historians believe it derives from the Etruscan word Apru (Aphrodite), celebrating Venus, the goddess of love and fertility. May was named for Maia, the goddess of spring and growth, while June honoured Juno, Jupiter’s wife. January celebrated Janus, the god of beginnings and endings. February, from februare (to purify), does not honour a god but derives its name from the Roman feast of purification known as Lupercalia (from the Latin word lupus, meaning wolf), which was held between the 13th and 15th of February. The purpose of the feast was to drive away evil spirits and purify the city, thereby promoting health and fertility.

July and August do not honour deities but were named after Julius Caesar and Emperor Augustus, respectively. July was originally called Quintilis (meaning ‘fifth’ in Latin, as it was the fifth month in the old Roman calendar) until the Roman Senate renamed it in honour of Julius Caesar, as it was the month of his birth. Similarly, August was previously named Sextilis (the sixth month in the old Roman calendar) but was renamed in honour of Emperor Augustus, who selected the month to commemorate several of his great triumphs. September (from septem, meaning seven in Latin) was the seventh month in the old Roman calendar, October (from octo, meaning eight) was the eighth, November (from novem, meaning nine) was the ninth, and December (from decem, meaning ten) was the tenth and final month of the year in the old Roman calendar.

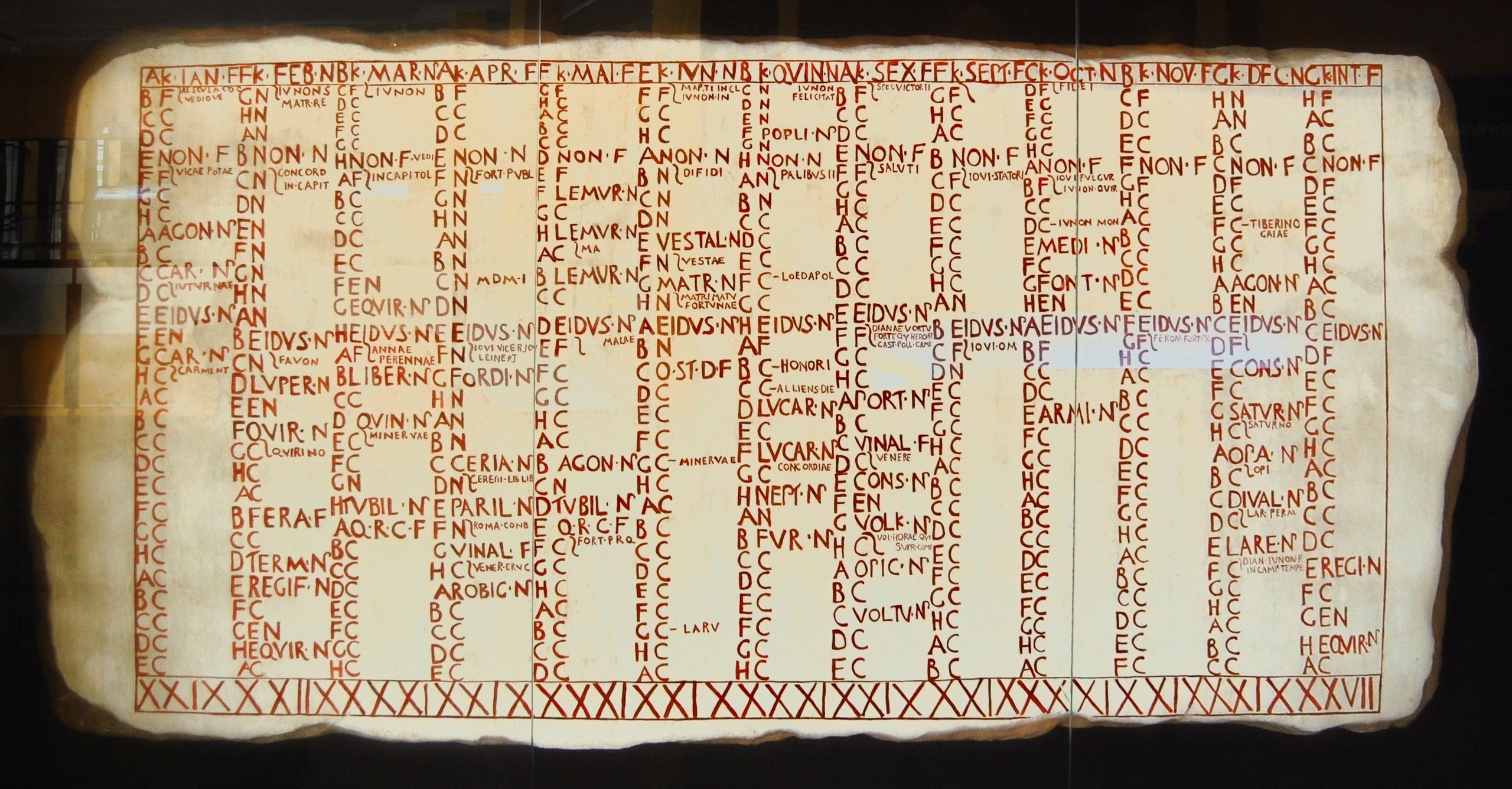

CC BY-SA 4.0 |

The old Roman calendar, prior to the Julian calendar, featured an eight-day week, much like the Etruscan system. This eight-day week was primarily a market week and concluded with a day known as the nundinum (related to the word novemx, meaning nine, as Romans counted days inclusively), when farmers brought their goods to the city's market. Before the introduction of the Julian calendar, the Romans did not name their days but instead labelled them with the letters A to H. One of these letters was designated as the nundinal letter, marking the market day. The nundinal letter shifted each year because the Roman year at that time consisted of 355 days, a number not divisible by eight.

When the seven-day week, with named days, was introduced alongside the Julian calendar, it coexisted with the eight-day week for a time. This dual system persisted until Emperor Constantine officially adopted the seven-day week in 321 AD. In this new system, Sunday was the first day of the week, and Saturday the last. Each day of the week was associated with a Roman deity.

Sunday (dies Solis) was dedicated to Sol, the god of the sun. Monday (dies Lunae) honoured Luna, the goddess of the moon. Tuesday (dies Martis) was named for Mars, the god of war, while Wednesday (dies Mercurii) was associated with Mercury, the god of commerce, communication, and travellers. Thursday (dies Iovis) celebrated Jupiter, the king of the gods, and Friday (dies Veneris) was devoted to Venus, the goddess of love, beauty, and fertility. Finally, Saturday (dies Saturni) was named after Saturn, the god of agriculture, renewal, and wealth.

In Latin-based languages such as Italian, French, and Spanish, the connection between the days of the week and Roman deities is still evident. For instance, in Italian, Tuesday is Martedì, and Thursday is Giovedì. Similarly, in French, Tuesday is Mardi, and Wednesday is Mercredi (the day of Mercury). These linguistic links demonstrate that the days of the week in these languages continue to honour Roman gods rather than Christian figures.

| Month/Day | |

| January | The eleventh month of the year in the ancient Roman calendar. In honor of the god Janus, god of the beginning and end. |

| February | The twelfth and last month of the year. From the Latin word februare to purify. In reference to the Lupercalia, the Roman feast of purification. |

| March | First month of the year. In honor of the god of war: Mars. |

| April | In honor of the god Venus. Comes from the Etruscan word Apru meaning Aphrodite. |

| May | In honor of the goddess Maia, the goddess of spring and plants. |

| June | In honor of the goddess Juno, who was the wife of Jupiter. |

| July | In honor of Julius Caesar. |

| August | In honor of emperor Augustus. |

| September | Initially the seventh month of the year. From septem in Latin. |

| October | Initially the eight month of the year. From octo or eight in Latin. |

| November | Initially the ninth month of the year. From novem or nine in Latin. |

| December | Initially the tenth month of the year. From decem or ten in Latin. |

| Monday | Dies Lunae, day of the moon and of the goddess Luna. |

| Tuesday | Dies Martis, day of Mars, the god of war. |

| Wednesday | Dies Mercurii, day of Mercury, the god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence, communication and divination, of travelers, boundaries, luck, trickery and thieves, and the guide of souls to the underworld. |

| Thursday | Dies Iovis, day of Jupiter, the king of the god and the god of sky and thunder. |

| Friday | Dies Veneris, day of Venus, the goddess of love, sex, desire, beauty, fertility, prosperity and victory |

| Saturday | Dies Saturni, day of Saturn, the god of generation, dissolution, plenty, wealth, agriculture, periodic renewal and liberation |

| Sunday | Dies Solis, day of the sun god Sol. |

How Romans Counted Days and Years

The original purpose of the calendar was to accurately time and plan various religious holidays. At the start of each month, priests proclaimed the new moon and announced the calends from the Capitoline Hill. They also declared the number of days until the nones and the ides, both of which were days of religious observance. The nones marked the half-moon and occurred six days after the calends in May, October, July, and March, but only four days later in the other months. The ides typically fell in the middle of the month and marked the full moon, always occurring eight days after the nones.

The Pontifex Maximus, the high priest of the College of Pontiffs and roughly equivalent to the modern-day Pope, had the authority to determine when a leap month (Mensis Intercalaris) should be inserted to maintain alignment with the solar year.

The Romans counted the days of the month very differently from how we do today. Modern calendars count the days after the first day of the month; for example, we say, "It is 22 June." In contrast, the Romans counted the number of days remaining until key dates such as the calends, the ides, and thenones. Instead of saying, "It is 22 June," the Romans would say, "It is the 10th day before the calends of July." This is because the Romans counted days inclusively, meaning they included both the starting and ending dates (in this case, 22 June and 1 July).

The Romans identified years by naming the two consuls holding office during that specific year. For example, they would say, "It is the year of Consuls X and Y." In the first century BC, Marcus Terentius Varro, an ancient Roman scholar and writer, introduced the AUC system (Ab urbe condita, meaning "from the founding of the City" in Latin). This system dated years from the presumed founding of Rome in 753 BC. The AUC system was widely used in the Roman Empire alongside the consular year.

Religious Holidays and Traditions

The ancient Roman calendar included numerous holidays, most of which were religious in nature. These included feriae stativae (fixed holidays) and feriae conceptivae (holidays with no fixed dates, whose timing was determined by the priests). One of the most famous holidays was Saturnalia, celebrated from the 17th to the 23rd of December. During this festive period, Romans indulged in feasting, exchanged gifts, and treated everyone as equals. Interestingly, when the Romans adopted Christianity, the tradition of exchanging gifts persisted.

Lupercalia, held from the 13th to the 15th of February, was a feast of purification. Its purpose was to expel evil spirits, purify the city, and promote health and fertility. February also featured the Feralia, a feast in honour of the ghosts of the dead. This association with the dead was one reason Romans avoided getting married during February.

Religious holidays were also observed in March and October to mark the beginning and end of the war season. Wars were typically conducted between these months, as favourable weather and sufficient food resources were essential. Another significant holiday was the Ambarvalia, a feriae conceptivae with no fixed date, which celebrated the arrival of spring and occurred around the time of modern Easter.

Interesting Facts About the Roman Calendar

|